My Reflections on the 2019 RSA Conference

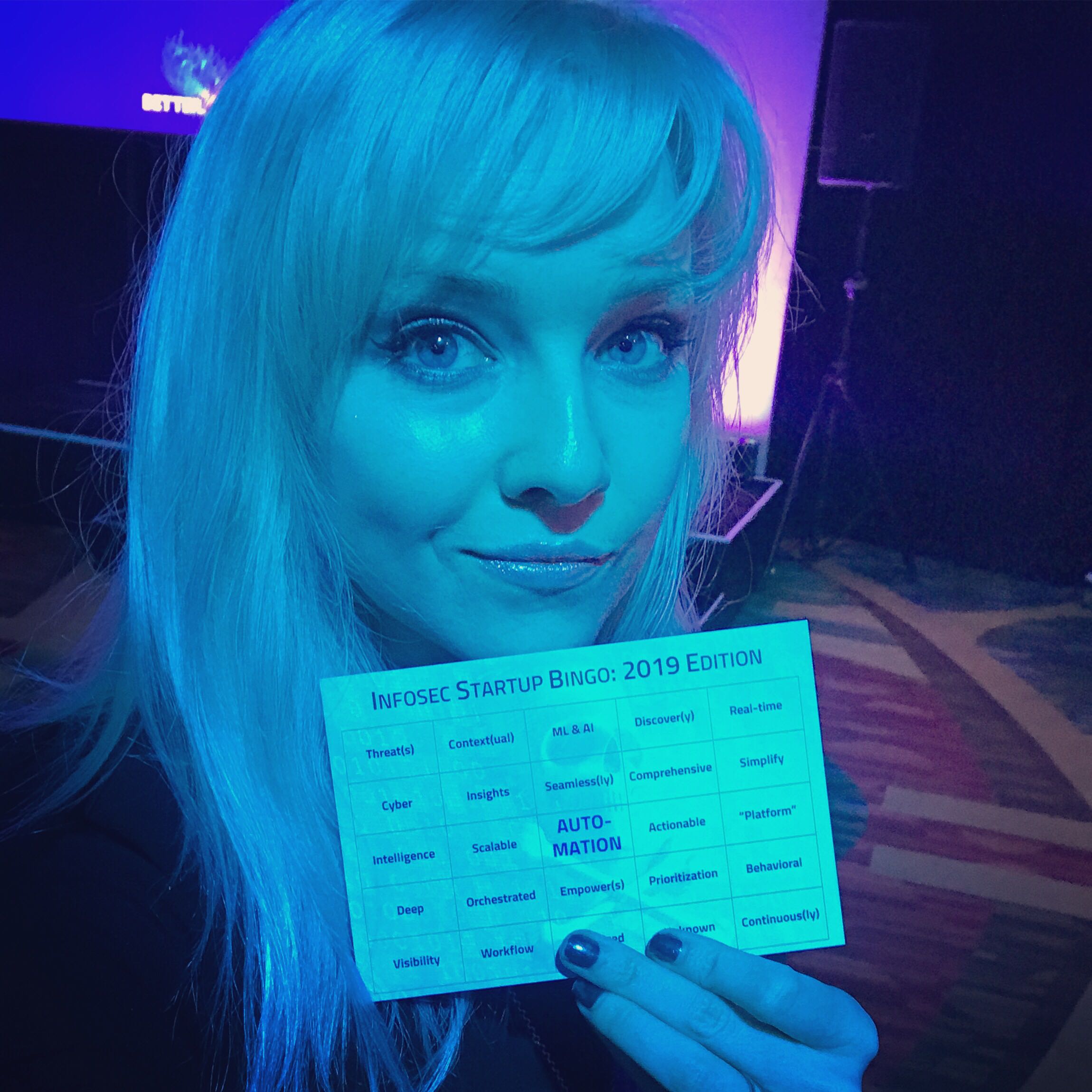

Artist’s rendition of how I felt by Thursday morning of the con

Artist’s rendition of how I felt by Thursday morning of the con

Reflecting on my existential crisis during RSAC, I tried to distill what exactly was so troublesome about the conference. The expo floor was less two separate halls, as per years prior, and more like Mordor, with a befouled sprawl connecting Minas Morgul and the Black Gate — but instead of orcs and Uruk-hai, vendors crammed the hallways that used to serve as open breathing space.

There was a dizzying sense of perpetual motion, like a spinning top just barely staying upright. Quiet was seemingly anathema — the pestilential cacophony of canned speeches and whizbangs and desperate pleas for attention was unavoidable.

In this vainglorious feast by the information security industry in dedication to itself, experiencing an existential crisis is perhaps an inevitability. The ultimate purpose of information security — ensuring an organization can thrive despite digital risks — was obscured beneath the thick layers of cheap pens dimly glinting, XL men’s t-shirts boldly proclaiming trivialities, and the hollow promises of soothing your fears one badge scan at a time.

But this alone can be rationalized away and not lead to a crisis of faith in the importance of our collective work. These criticisms are true for most trade shows; they are inherently loud and sales-y. What makes the RSA Conference burrow into the brain like a parasite greedily devouring all hope is that the diabolical song and dance is not helping beneficial solutions fall into the right hands.

RSAC is largely successful due to network effects — because everyone seemingly attends, everyone else attends — making it a good place to catch up with a lot of people at once. This reality makes its issues even more problematic; the four that personally drove my distress are:

- Hyperbolization of FUD

- Disconnect between products & personas

- Misunderstanding of personas

- Promotion of security as a blocker vs. a compromiser

Hyperbolization of FUD

In a banquet of distasteful and inane catch phrases and bullet points, one gave me acid reflux like no other—it exemplifies what I am calling the hyperbolization of fear, uncertainty, and doubt (“FUD”). A large EDR vendor’s advertisements around town roughly stated, “It takes a lifetime to build your career, and 5 seconds to lose it.”

There was no shortage of FUD around threats, but this tagline directly stokes the fear that someone’s professional life will be over if they let an attacker slip by. It’s tasteless and mostly incorrect, and I find it appalling to imply that someone’s life will be ruined if they don’t buy your product. I also find it lazy; if you can’t sell your product without scaring people to such a degree, perhaps you should make your product inherently matter more to them.

Part of the issue might be that the industry is generally poor at realistic threat modelling, making these doom and gloom buzzphrases compelling. While it’s too much to hope that all vendors could help their customers threat model responsibly, I believe it’s a reasonable expectation to not aim directly at personal fears and not make up scenarios that lack precedence in history or logic. If a vendor must create dystopian sci-fi to justify use of their product, they are doing it all wrong.

Disconnect between products & personas

My first supposition with regards to the persona problem was a disconnect between buyer and user personas. Specifically, that narratives around usability seemed to be keeping the buyer (CISO) in mind, rather than the people who would actually use it (individual contributors (“ICs”). Upon reflection, I think it’s worse than this — that there is a disconnect between the buyer personas and the vendors’ target audience.

By this I mean that the marketing tactics, highlighted characteristics, even the words used all feel targeted towards other sales and marketing professionals, or perhaps venture capitalists (“VCs”). During the conference, I spoke with a large swath of practitioners ranging from CISOs to managers to senior ICs to more junior ICs, and none of them found the booths enlightening or particularly worthy of their attention.

This begets the question — for whom is all this marketing? My prior assumption was that vendors would target the buyer persona (generally the CISO or director/manager-level) at the very least, since they are the people spending the budget. Ideally vendors would also target ICs, who are the ones actually using the product, and whose thumbs up is generally required by the buyer.

But given none of those personas felt addressed by vendors at the RSAC expo hall, who did? To be perfectly frank, I’m not entirely convinced of the answer, but my hunch is that:

- VCs are dictating marketing/value propositions too much, particularly given they are generally disconnected from customer viewpoints

- Marketing people are generally too disconnected from customers & don’t really understand the relevant personas

- Infosec is generally horrendously bad at understanding the spectrum of relevant user personas

Misunderstanding of personas

Point #3 above leads to this observation, which is that vendors overall seem to egregiously misunderstand the personas for which they are allegedly building their products.

As I discussed in my TechCrunch article, vendors are building tools and determining the specific problem being solved after the fact — often leading to the need to convince customers that the vendor-invented problem is relevant to their organization. This trend of focusing on tech rather than customer problems extends, I think, to vendor-invented personas, as well.

If you were judging solely based on the RSAC vendor floor this year, you might think the most important user persona in infosec is “SecOps.” There’s little differentiation visible in this “persona” between a SOC analyst straight out of school analyzing low-priority events vs. a SecOps engineer who writes automation scripts for things like distributed alerting — not to mention a SecOps manager vs a SOC manager and the chromatic variation around all of these titles. And, is their purview just DFIR or other responsibilities, too?

This isn’t to say generalized personas aren’t useful — but I’m wondering if vendors are now treating SecOps as the “person who deals with security events.” If so, then most people in infosec are kind of SecOps depending on how you define “event,” which would thus render SecOps a meaningless term given how different everyone’s workflows are across the range of roles.

Additionally, there were impressively lazy attempts at catering to the DevOps and so-called SecDevOps personas. Security vendors seem to think that making their product available via API means they “integrate with DevOps workflows,” which is either amazingly apathetic or oblivious.

There was also lip service paid to working with existing CI/CD pipelines, but then security vendors still expect DevOps people to go through 20 additional hoops, not realizing that they simply won’t. For instance, please don’t claim you are DevOps-friendly while asking them to install a kernel module on every machine they actively use.

This leads to my assumption (and into my next point) that security doesn’t realize how immaterial they are relative to a team (DevOps) that can justifiably argue that they support revenue-generating activities. And, what’s worse, vendors provide little support for their customers to fight for security’s inclusion in the conversation.

It as if vendors expect that by saying “we secure the development lifecycle!”, security practitioners can convince the organization to install their product. This notion of a security team having the keys to an organizational steam roller is, of course, pure fantasy.

Promotion of security as a blocker vs. a compromiser

Finally, I think infosec is largely ignoring an important emerging shift, which I believe is inevitable — the transition from security as the “no people” to enablers of the business. Enterprise security only matters to the extent that it is helping preserve the company’s ongoing operations. Anything beyond that feels largely like intellectual vanity to me (this is precisely why I’ve been evangelizing the notion for a few years now).

How does this play into RSAC? I argue that the most successful security vendors of late are about removing barriers, in contrast to many security people believing barriers are worthwhile aids in their infosec crusade (and I also suspect that creating organizational barriers provides significant vocational fulfillment among a chunk of security professionals).

To wit, zScaler consolidated old products and made it easier for the organization to access resources without the tedious VPN dance. Okta likewise streamlined access and made a lot of enterprise workflows simpler. Both are now trading at delectably rich multiples (both above 20x EV/Revenue) — a victory even beyond the fact that they are some of the few information security startups to IPO in recent years.

Ultimately, anyone can say “no” to something —but just saying “no” isn’t actually solving a problem. Figuring out a compromise, like preserving or even improving UX while still ensuring an organization’s security, is a hard problem — the type of problem which should be most intellectually fulfilling.

Security will keep being dismissed by other parts of the organization until it lets go of finding fulfillment through security righteousness and instead finds fulfillment by finding an elegant way to enable the business while still reducing its risk.

One of my favorite examples to cite is John “Four” Flynn and the tale of implementing 2FA on SSH at Facebook. The security team conducted product-like user research interviews across engineering teams to figure out how SSH was being used — essentially mapping user workflows. The security team’s goal was to add 2FA to SSH, but instead of ramming it through like petulant ayatollahs, they sought to understand the user perspective and determine a solution that would not add friction for engineers.

It was a hard problem, but with a huge payoff; now the engineering teams can trust that security isn’t just trying to make their lives more difficult for sport or quasi-religious fervor. This means the relationship can be more like a partnership, rather than a political battle — the sort of battle security practitioners allegedly detest (likely because they tend to lose it).

Conclusion

These issues are not engendered by one constituent of the industry — they just all happen to notably bubble up like a tar pit burping methane in the harsh fluorescent spotlight of RSAC. It is the failure of culture among practitioners, vendors failing to understand their customers’ needs, founders going for cash grabs, and VCs encouraging the noxious sleaze and bamboozlery.

All of this comes, perhaps, from a reticence towards doing the harder, right thing and instead taking the easier path — the one that harvests confusion and fear to seize success that mediocrity could not earn otherwise.

I speak a lot about incentives, and, in fairness, there is an abundance of incentives rewarding this mediocrity, but far fewer promoting the more difficult path. CISOs don’t want to speak out against vendors and, in fact, benefit when they are seen as essential in navigating not just the threat landscape, but the vendor landscape as well. Vendors can still find decent M&A exits that make founders and investors happy enough, even if they sell solely within their professional networks and don’t ever find true product/market fit.

And if VCs make enough money from this buffoonery, why should they bother to understand the customer personas better to inform their investment choices? Many VCs have CISO friends, but I know from private conversations that these CISO friends often view the VCs as useful fools who can help them gain advisory or board positions.

If it sounds hopeless, well… I’m not sure it isn’t. But I refuse to give into nihlism. There are absolutely those of us who are fighting to change things, but there is a lot of entrenched power which benefits from keeping these dynamics the way they are in information security.

It will take those willing to risk their power to speak out in the truest form of thought leadership there is. Speaking into a warm and fuzzy echo chamber isn’t thought leadership; bravely challenging the status quo, armed with evidence, is.

We can keep the corporate-friendly cerulean and navy aesthetic, the blustering loudness, and yes, even the free pens, but we need to dedicate these efforts not to the thrill of our industry finally being considered “cool,” but to solving hard problems and protecting organizations in the way they need.