Shortridge Makes Sense of Verizon’s 2025 Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR)

Every year Verizon publishes our collective best attempt at collating real-world evidence of attacks in the 2025 Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR). It is either my privilege or curse as notorious cyber raconteur and rapscallion to yet again receive an advance copy1 of the report to digest and distill.

What follows is my commentary on the Verizon 2025 DBIR, attempting to make sense of this year’s data and share this sensemaking with the community.

As ever, I remain a skeptic and scientist, seeping in the systematic doubt of the Socratic method. The Verizon DBIR team readily acknowledges2 that this data cannot reveal the full dynamics pervading incidents and breaches.

The report polishes disparate tiles from data sources – some ceramic here, limestone there, glass, marble, a veritable jumble – and adds pieces to the industry mosaic, incomplete, but nevertheless an incremental step forward towards Truth.

Well, as close to Truth as the travesty that is VERIS allows.

Let’s dive in.

1. So what?

Why does any of this matter?3 When you strip away the sublime sensation of “OwO new shiny data!!” to which all humans succumb, how does this data add value?

Simply put: what is the impact of the incidents and breaches enumerated within? Impact’s absence throughout the report in some sense recalls Ozymandias, that seething expanse of desert, primordial dunes swept and sculpted by eternal winds – that profound existential emptiness found in the colorless abyss of slipshod content that perhaps, most of all, defines our current times.

A little bird told me that the DBIR team yearns to ingest cyber insurance claim data, and I, too, yearn, so, please, if you are in a position to provide it, do so.

For it is in the “what actual $s €s £s did insurance companies pay out for incidents with X attack vectors or Y assets?” that we will learn where optimal ROI resides – both in the micro and macro.

Imagine if we could see just how much these incidents and breaches cost insurance companies in claims – then compare that with the collective spend on vendors, security teams, and the other elements that make up titanic (albeit, this year, often flat growth) security budgets.

For 2025 in particular, it is worth asking: did the Crowdstrike outage’s impact on businesses (or society more generally) outweigh all the breaches in this report combined? Very rough calculations – truly extremely untrustworthy math4 – from the report imply ~$2.66bn in damages from Ransomware attacks. But the Crowdstrike outage cost Fortune 500 companies at least $5.4 billion, or $44 million per Fortune 500 company.

This ignores the indirect costs imposed upon the populace across sectors – like those saddled on travelers due to cancelled flights. Nearly 17,000 flights were cancelled during the 72 hours after the outage. How do you quantify the cost of a family member missing a funeral due to cancelled flights?5 How do you quantify the cost of a loved one missing a critical medical procedure?

The core question is: should we be allocating more or less effort to cybersecurity – and where should we be allocating those efforts more or less? The report cannot really answer this without tying these statistics to tangible costs and benefits.

It calls to mind the classic quip, “Half my advertising spend is wasted; the trouble is, I don’t know which half.” As anyone in advertising will divulge, presuming we only waste “half” is a generous estimate.

To the well-meaning cybersecurity professionals among you, how do you intend to use this information? How will it inform your choices? How will you investigate how these trends align with what matters to your business? Consider these questions as you continue reading this commentary.

2. Espionage: fast fashion or couture?

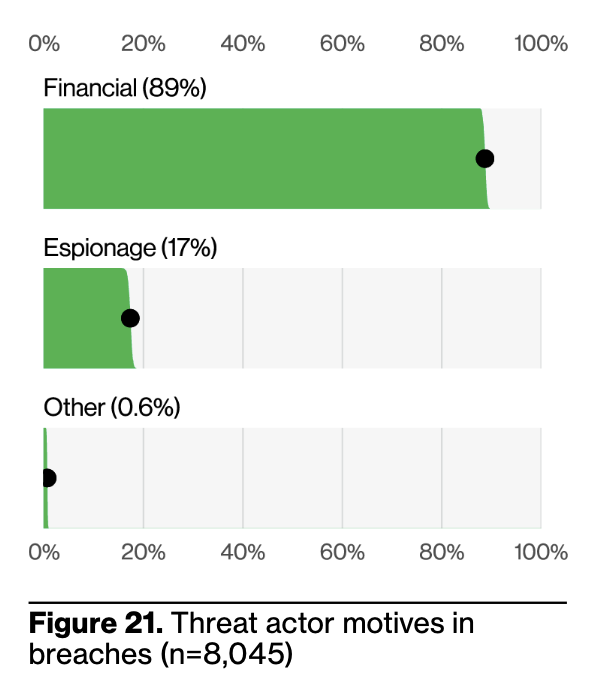

The 2025 DBIR features new contributors that added much-needed data points related to “espionage” events, i.e. those conducted by nation state-affiliated actors. This figure shot up to 17% (as shown in Figure 21 from the DBIR), much to the delight of FUD-driven GTM teams who will soon descend on Moscone, I’m sure.

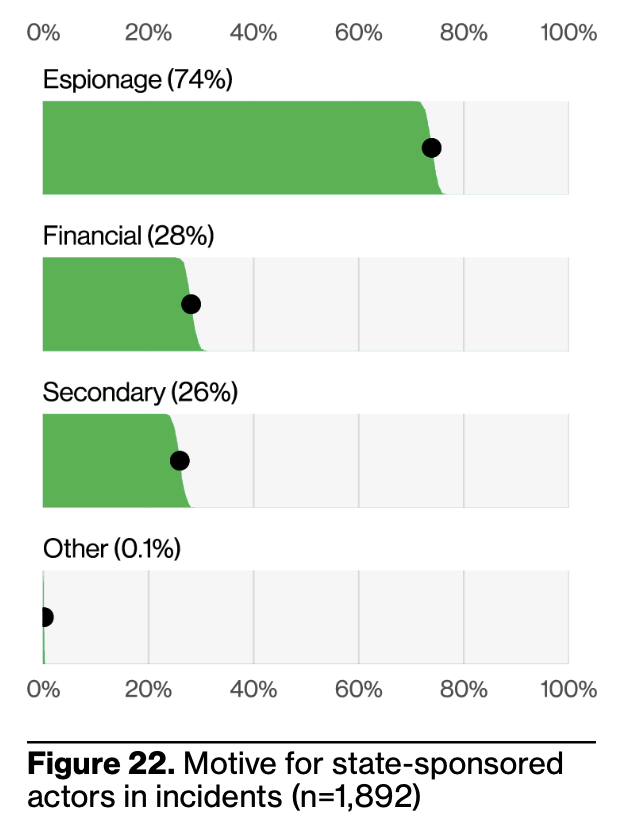

However, many of those espionage events also feature financial motives. Why might that be? Shouldn’t nation states be sufficiently flush with cash and coin that they need not stoop to monetary theft?

Well, depending on the nation state, sanctions suck and make it hard to transact at financial institutions. Or, if you’re a nation state who wants to save face on the geopolitical stage, it’s far better to spend someone else’s money – especially if in the form of cryptocurrency – to enhance plausible deniability.

Many nation states prefer to slink and prowl through the ferns and fronds of software systems, abscond in shadows, slip past moonlight and crisp branches to avert the treacherous crunch that would startle their prey. Unlike successful ransomware-aaS startups6, nation states don’t need to run marketing campaigns to differentiate and drive demand for their services.

In general, nation state actors would like to preserve their access into target systems for as long as they can (a point to which we’ll return shortly), or else achieve other nearer-term goals in service of the longer-term mission. Being mistaken for a “nuisance” or petty criminal may hurt their pride, but, unlike too many traditionalist blue teams, they can put that aside for their mission.

These missions pile up expenses. Every attack group still must consider costs. There is no tree on this planet that grows money (though we can burn them en masse to mine cryptocurrency, true).

APTs need hardware to mount attacks, new IPs to evade detection, compute to run workloads. Those things cost money. Even money laundering costs money. For some of these things, like compute, they can steal from organizations so it comes from someone else’s wallet, not their own – but this thievery alone cannot sustain their ongoing operation.

Attack operations, like any business operation, require an intricate support system to keep running. And, like most business operations, to get more funding for your team, your mission, your whatever, you must appeal to the authorities above you.

From that perspective, is it not obvious why nation state actors would commit financial crimes? Maneuvering through someone else’s machines is easier than maneuvering through the humans who control your budget7.

so, tl;dr Your threat model is still predominantly money crimes.

What does this – still admittedly minor – presence of espionage mean in practice? Why does “nation state pursuing financial crimes” matter as a distinction from “cyber criminals pursuing financial crimes”? Do their methods differ so much that we need different defenses in place?

Not really.

The distinction grabs attention but is not where our focus should lie. The more relevant question is: what is the essential element of my business that makes me a target? As in, if I make it harder, are attackers going to bother someone else, or do they want me specifically for some reason?

Simply put: we should stop worrying so much about who the attackers are, and more about who we are; what makes us special, rather than what makes specific attack operators special; how our differentiation, competitive dynamics, and market strategy reveals more “threat intelligence” than whether the attacker prefers bamboo or wood pulp TTPs.

If you die in a sophisticated attack vs. a crude one, you’re still dead.

Attackers are not stupid, but they often spend their effort on relatively stupid (or “simple”) techniques. I, too, will often take the trash panda, “lazy” way8 rather than taking the higher-minded, effortful way unless necessary, and I suspect you, dear reader, can also relate.

The Gayfemboy botnet operators epitomize this impetus to evolve only as necessary. To wit, XLab observed:

However, the developers behind [the gayfemboy botnet] were clearly unwilling to remain mediocre. They launched an aggressive iterative development journey, starting with modifying registration packets, experimenting with UPX polymorphic packing, actively integrating N-day vulnerabilities, and even discovering 0-day exploits to continually expand Gayfemboy’s infection scale.

I certainly count the Gayfemboy botnet as “sophisticated” on these grounds9. I also think the Salt Typhoon campaign showed sophistication. I don’t think what the DBIR – and, certainly, the broader ecosystem – characterizes as “sophisticated” is necessarily so.

It raises a valuable question: what does sophisticated mean in the context of attacks and cybercrimes? Sophistication, definitionally10, involves flavors of:

- Understanding how things really work

- High quality or reflecting a high level of skill

- Refined taste

- Rizz11

That first characteristic – understanding how the world really works – implies that sophisticated attackers will be those who adapt their techniques based on what works; sophisticated attackers won’t waste their finite time and effort on techniques that don’t.

From the attacker’s perspective, if they perform one big, flashy display their target quickly detects, now they’re dead. If they take consistent action to maintain access in their target systems for years, but those actions are “simple” or “stupid” – well, they’re still alive.

If we find someone persisted in our network for years using bash, after exploiting one lucky, exposed N-day vulnerability – maybe that is sophisticated.

Sophisticated is more about the attacker’s “broader goal” – their roadmap, vision, and ability to execute on it, if you will – rather than about the means they employ. Can an unsophisticated actor turn stolen credentials into a one-time smash and grab? Certainly. But can that actor turn those stolen credentials into getting in, and staying in, forever? Probably not. That is the hallmark of a sophisticated actor.

Perhaps an appropriate definition of “sophisticated attack” refers to how hard we must work to detect it. If we list admins and see new ones, that’s an APT TTP corresponding to MITRE ATT&CK blah blah, but that’s not very hidden, and thus not very sophisticated.

“Sophisticated attack” vibes are like, someone smart cared about this attack operation, and that’s spooky because it means they had a purpose. What was that purpose? Hence, we return to the key question of: what is the essential element of my business that makes me a target?12

If we apply this line of reasoning to defense, does it not imply that “sophisticated” security strategies are those that prioritize consistency over flashiness? That take incremental action to adapt and persist in their mission of preserving the values their business treasures most (like revenue, profitability, or DEI)?

3. APTs go BWAAhaha >:3

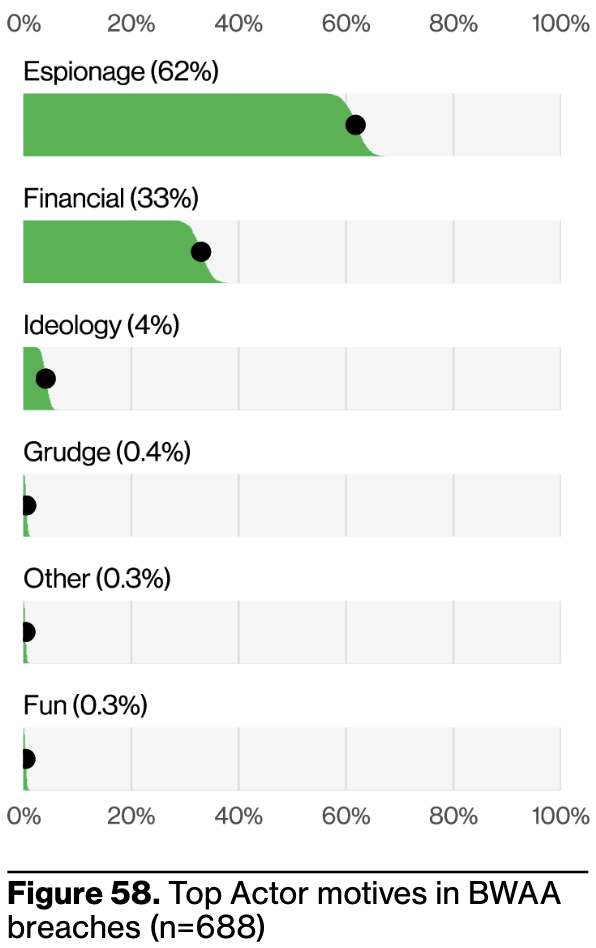

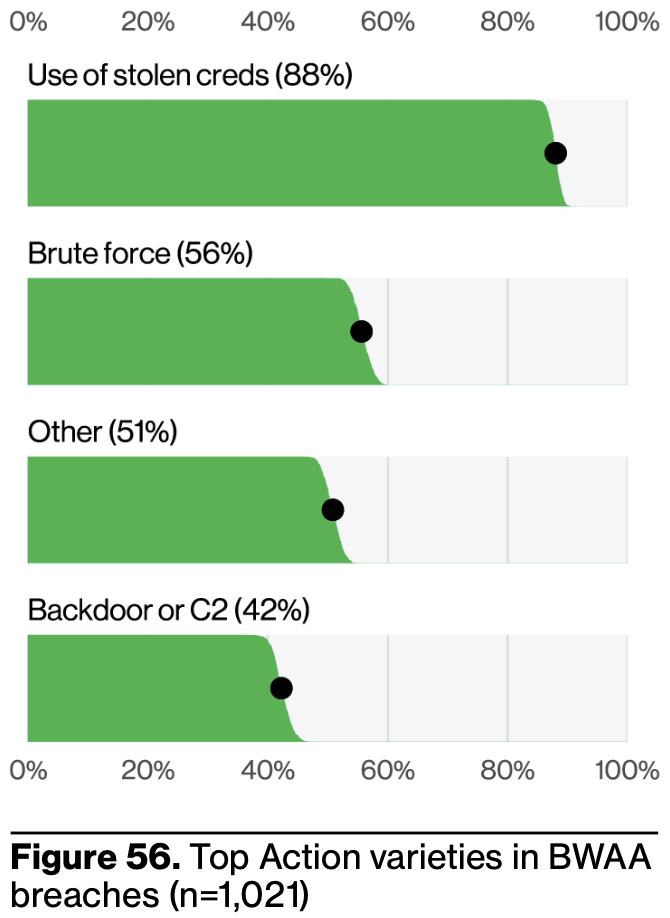

One insight that might surprise many readers in the 2025 DBIR is that Espionage-flavored actors account for approximately 62% of Basic Web Application Attacks (BWAA), up from 10 - 20% historically (largely due to the 2025 DBIR’s data contributors proffering more espionage in their data set).

As nation states largely conduct espionage, this means oft-aggrandized APTs are booping and bopping your web applications to see what works before they escalate their efforts. Their workflow, not unlike most professional cyberattackers, goes something like:

- doodle around in shodan

- look at some banners

- (optional step: ingest more caffeine)

- ponder, “what is that, anyway?”

- google it

- download source

- fuck around

- get a shell

- throw in the wild

- some extra steps the industry mostly ignores, anyway

- profit / geopolitical advantage

As I stated in my last section, being sophisticated is expensive and time consuming (as any 12-step skincare girlie knows all too well). It is still really smart for APTs to try the easier path of BWAA – but it also, hopefully, demystifies them (a good thing; the industry should never have mythologized them in the first place).

“But, but,” you’re thinking, “BWAA is just the vector for them to gain access to the underlying server and pivot!”

I asked this question to the DBIR team, and they clarified that BWAA refers to messing around at the app layer itself (like XSS), while “System Intrusion” reflects app exploitation to gain access to the underlying server (like Command Execution). I find this distinction fuzzy and frustrating, and another reason why I dislike VERIS. SQLi technically messes with the interaction between the app and the database, but counts as BWAA.

While I’m ranting here, I’ll also lament that they don’t track “abuse” as much as perhaps they should. What I hear from platform eng and security eng leaders alike is that the web app and API abuse events plague them most in terms of impact.

Anyway, my venom for VERIS aside, this data point likely means nation states view these layer 7 gallavants as lucrative enough to try. An individual BWAA attack may not spill out a platoon of candy from a single app piñata, but if you can mount such attacks at scale, against many apps – which, one would hope a nation state subpod could develop such a capability – then they manifest their own whole ass Candy Land.

Through the lens of crimes of geopolitical passion (i.e. espionage) vs. money crimes, this trend perhaps also reflects how the world now conducts so much business via web apps. It’s Snowflake, Salesforce, Hubspot, Zoom, and Google Docs that vampirize our working hours, not desktop software13. Web apps now hold the trade secrets, the sales projections, the strategic plans, product roadmaps, financials forthcoming in an SEC filing.

Do nation states learn about and understand market trends faster than blue teams? Why do attack groups seem to experiment with and adopt emerging technology at the same time blue teams resist those innovations?

Bonus points if you ask these questions at an RSAC cocktail party as a conversation opener.

4. How do the money crimes generate money?

If most attacks – conducted by criminal organizations and nation states alike – involve financial motives, how do attackers convert those incidents and breaches into money?

The DBIR does not have many answers for us (nor is it their fault they do not), but it is, nevertheless, a worthy question to explore with the data they do present.

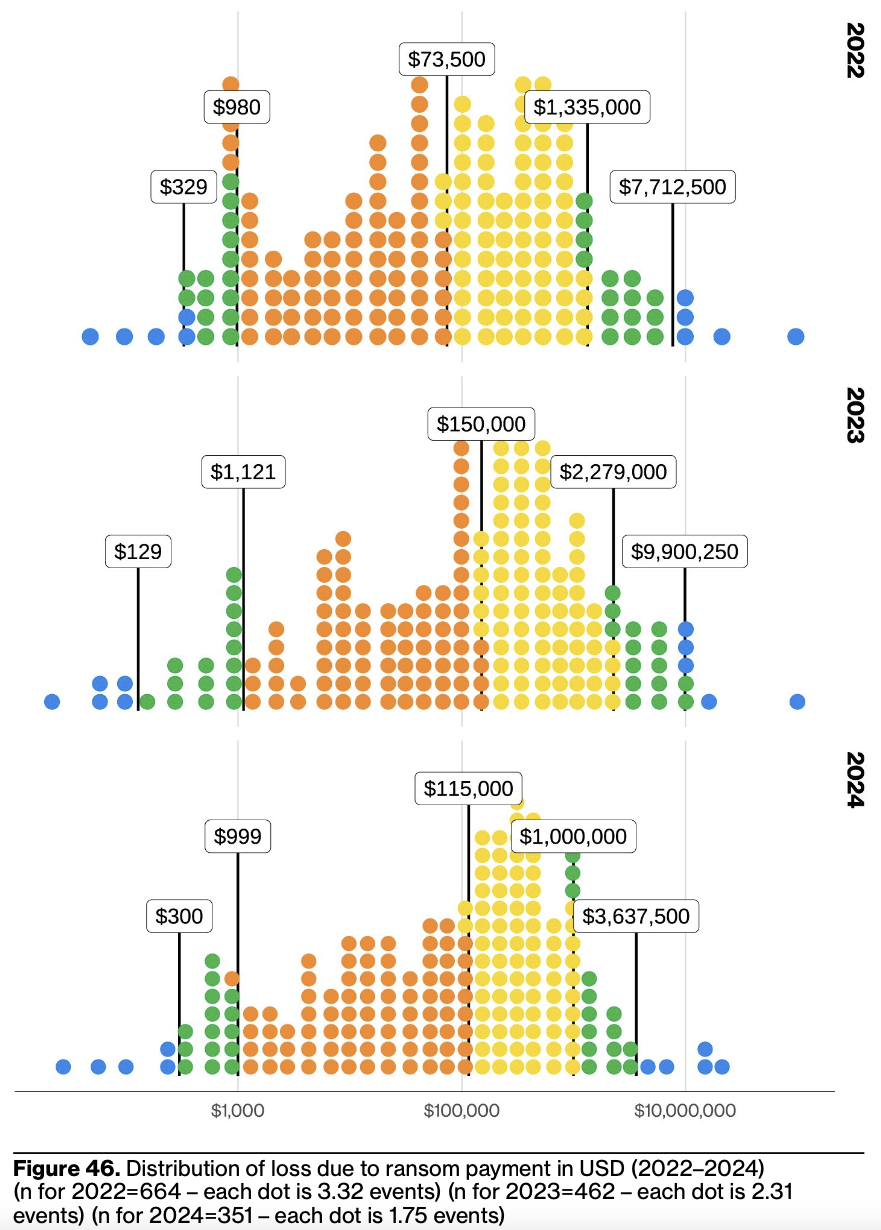

Ransomware is our obvious place to begin. tl;dr payouts are shrinking, and fewer organizations are paying any ransom at all (especially larger enterprises).

Are we improving at system restoration and disaster recovery? Or, alternatively, are the consequences of leaking customer data not actually that bad in practice?

Ransomware’s monetization path feels obvious, and some criminal entrepreneurs have executed that GTM strategy very well14. So, no surprise that there are no surprises in the report on the ransomware front.

The real mystery to me is why we keep seeing DDoS attacks? How are attackers even monetizing it enough to justify the effort? Why do they still try given they don’t succeed very often? These questions vex me15.

A lazy hypothesis might be that attackers are stupid. Some are stupid and delulu, like any arbitrary group of humans, but I don’t think that explains this dynamic.

Ignorance is the more plausible explanation. As in, there are absolutely nation state actors who live in their nation state bubble and don’t participate in “hallway tracks,” or casually chat with private sector tech pros, or gain any other experience other than in classified government settings. The same goes for organized criminals in locales lacking high-scale digital businesses.

There are a lot of people out there who are in relative positions of power now who may earnestly think, “oh, if I get an X gbps botnet then I can hold some digital terrain at risk!” They are probably wrong, because they do not understand CDN capacity and capability in 2025. They may not even understand CDNs exist, or that most enterprises use them16.

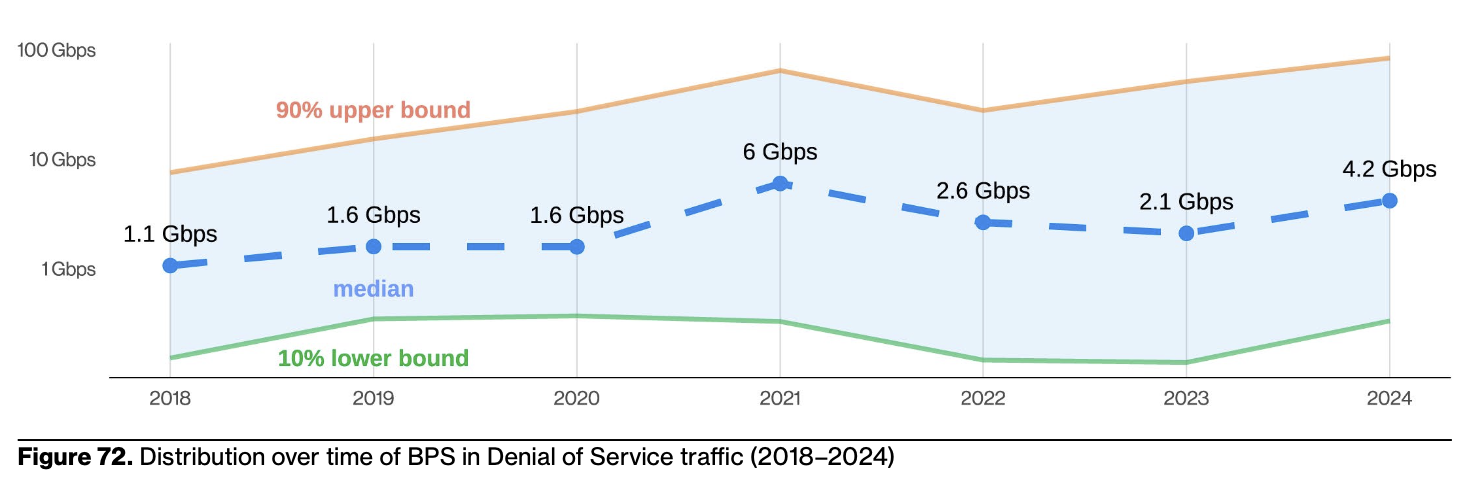

With that said, it’s true, based on the figures in this year’s DBIR, that most enterprises could not withstand or mitigate availability attacks on their own.

These numbers boggle the mind; scrombulate the brain, if you will. DoS attacks of this size mean that you, a typical enterprise (let alone an SMB), really can’t run a site or service on more modest infrastructure without expecting a DoS to take it out.

These figures mean you really must use an infrastructure provider that has enough scale and pay for their DDoS protection because the packet and bandwidth rates of the largest attacks are astronomical.

I must disclaim here that my Business Cat day job is serving as VP of Security Products at Fastly, who indeed is one of those infrastructure providers that provides CDN + the requisite security needed to ensure shit doesn’t go wonky when you deliver software on the public internet.

Even so, when I asked the DBIR team why they haven’t paid as much attention to network-based availability attacks, they – like many in the industry – view this as a “solved problem,” in the sense that everyone uses a CDN or CSP now to handle DoS mitigation.

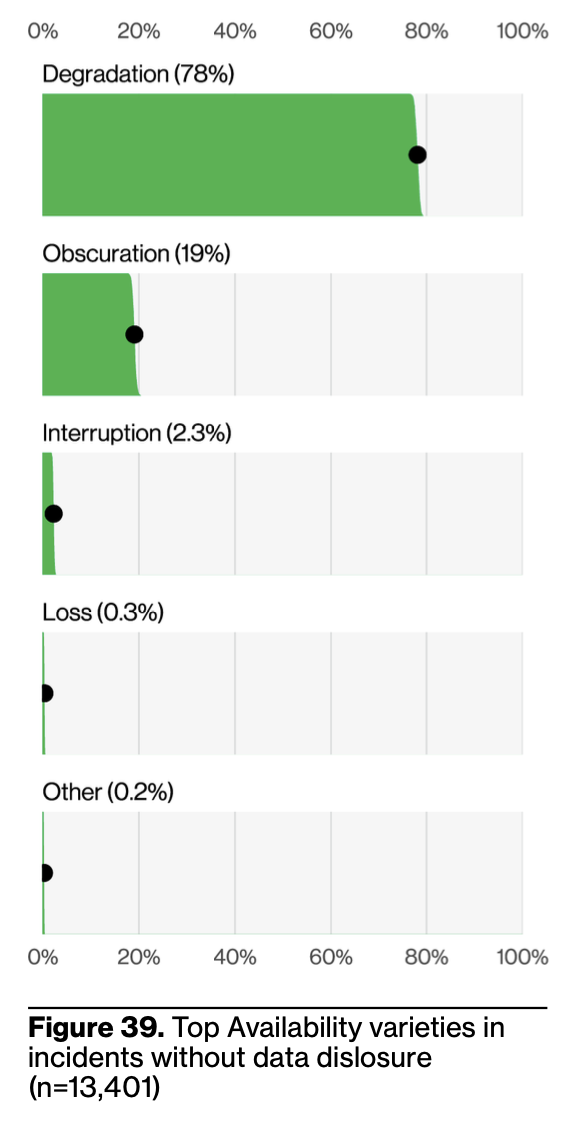

There’s truth to their view, and also that, based on this data, this strategy seems to work pretty well. I found it fascinating to learn that only 2% of availability incidents (mostly DoS) lead to service interruption. Even degradation shows some level of resilience against attacks, too.

Of course, it’s worth asking: how many DoS attempts were there that could not foment sufficient damage to receive the designation of incident?

The prevalence of degradation also reflects of the nature of modern systems. We aren’t building monoliths anymore, so attackers may only succeed in taking down a part of a system – a blip rather than a blammo, so subtle that many users won’t even notice.

The flip side of this evolution away from monoliths is that it might be easier for attackers to disrupt or degrade a critical component that receives less traffic, like your cart checkout page, which will anger your customers and executives alike.

How much does that kind of targeting (and hypothetical impact) happen in practice? I hope next year’s DBIR might answer that question.

Another hypothesis is that not all criminals are good entrepreneurs. Some are quite poor at the business side of crimes, which, naturally, softens their ability to penetrate the multi-billion dollar cybercrime TAM.

Cybercrime vendors, much like cybersecurity vendors, depend on brand awareness to succeed. Sometimes they are quite bad at conceiving and executing marketing campaigns – which, from what I’ve observed, is sometimes a sign they aren’t super great at identifying product/market fit, either (as in cybercrime as in b2b tech, luck plays an enormous factor, and you can stumble into success without ever truly understanding why).

My favorite example of criminals fumbling the bag in clumsy attempts at entrepreneurship appears in the U.S. Department of Justice’s indictment against Anonymous Sudan from last year (June 2024).

Defendant AHMED OMER and UICC 1 would post messages on Telegram in channels they controlled claiming credit for these attacks, often providing proof of their efficacy in the form of Check Host reports showing that the victim computers were offline.

Their claims often did not match the reality. For instance, when they tried to DDoS Netflix and only disrupted a few regions of service, they claimed Netflix was “strongly down.”

Or, in another instance:

Overt Act No. 101: On May 22, 2023, defendant AHMED OMER sent private messages on Telegram stating, “check https://oref.org.il, if you find backend im ready to pay u good money.” The other party then sent AHMED OMER an IP address, to which AHMED OMER replied, “I fuck this ip but www.oref won’t down.”

“I fuck this IP” is lowkey iconic as a pro-DDoS product slogan, but this message, along with messages that provide an IP and ask “how to down?”, perhaps does not instill a sense of confidence in their target customer base.

While originally motivated by ideology and national pride, Anonymous Sudan tried to monetize their operation over time, including creating an automated bot to collect payments from victims seeking a ceasefire:

We can negotiate a price with you to halt all DDoS attacks immediately, and help you apply DDoS mitigation. To negotiate, contact us at our bot : @AnonymousSudan_Bot.

It is unclear to what extent they ever monetized these attacks. They claim to have in some cases, like:

On March 5, 2024, defendant AHMED OMER or another co-conspirator posted a message on Telegram stating, “After more than 48 hours of holding the Zain Bahrain network offline, we have finally reached a deal with them. Therefore, we’ll stop all attacks on their networks immediately. This entire experience proves the revolutionary power of @InfraShutdown team in holding huge networks for days and getting multi-billion companies to their knees. You can request an attack of any scale and unlock this never seen before power by contacting @InfraShutdown_bot.

But, well, do you believe their claims based on these messages?

Perhaps that’s the most common ground blue teams can find with cyber criminals: whether Telegram, or SoMA during RSAC, both of their bubbles drown in grandiose claims.

5. Attackers are still not really using GenAI

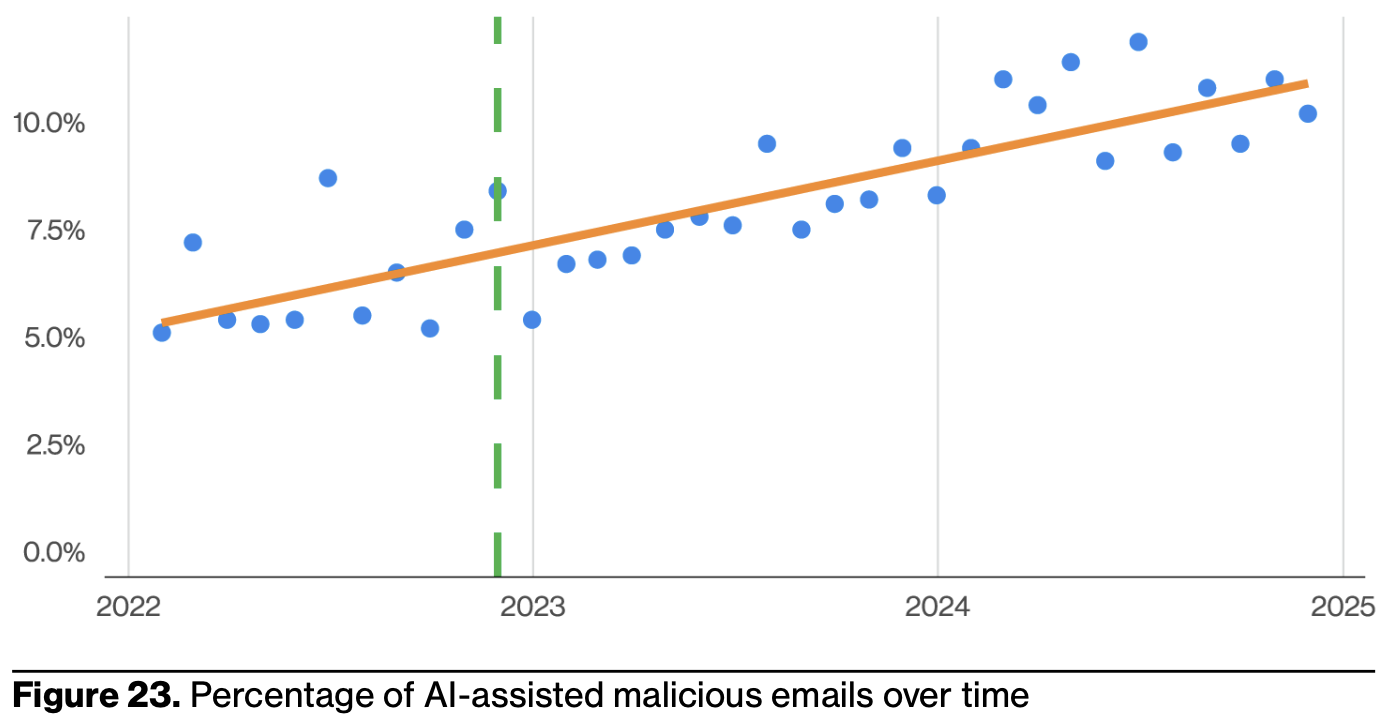

Last year, I noted that attackers aren’t using GenAI. They still aren’t, really. And when they do, it doesn’t seem to make much of a difference.

Specifically, GenAI hasn’t really made phishing “better” in some sense, because it’s still down in relative prevalence. How much of an asymmetric advantage does it really offer attackers? I suspect GenAI provides more ROI for aspiring CISO thought leaders on LinkedIn than most attackers, although the former means the latter can create their own fake aspiring thought leader CISOs for more credible social engineering.

Alas, if the DBIR hadn’t investigated GenAI involvement in incidents and breaches, I’m sure the AI evangelicals enthusiasts would’ve slandered them with, “you’re missing the LLM impact! It must be huge!” I take its inclusion as the report-writing equivalent of bequeathing someone a token object upon your death in your will so they can’t claim they were inadvertently left out.

This isn’t to say GenAI isn’t used anywhere; it clearly is, but it seems not to have improved efficacy over the previous techniques. Writing spam email with fancier LLMs instead of more basic ML doesn’t necessarily improve deliverability or fidelity.

As a final note on GenAI, since I’m sure some VC or startup bros are already thinking “but wait, what about –” no, the data set doesn’t include any real-world attacks on LLMs themselves. Maybe this will be present in next year’s data set now that people are wiring LLMs to their proprietary data sets and letting them roam as free range models with minimal supervision.

6. If you can’t make your own 0day, store-bought creds are fine

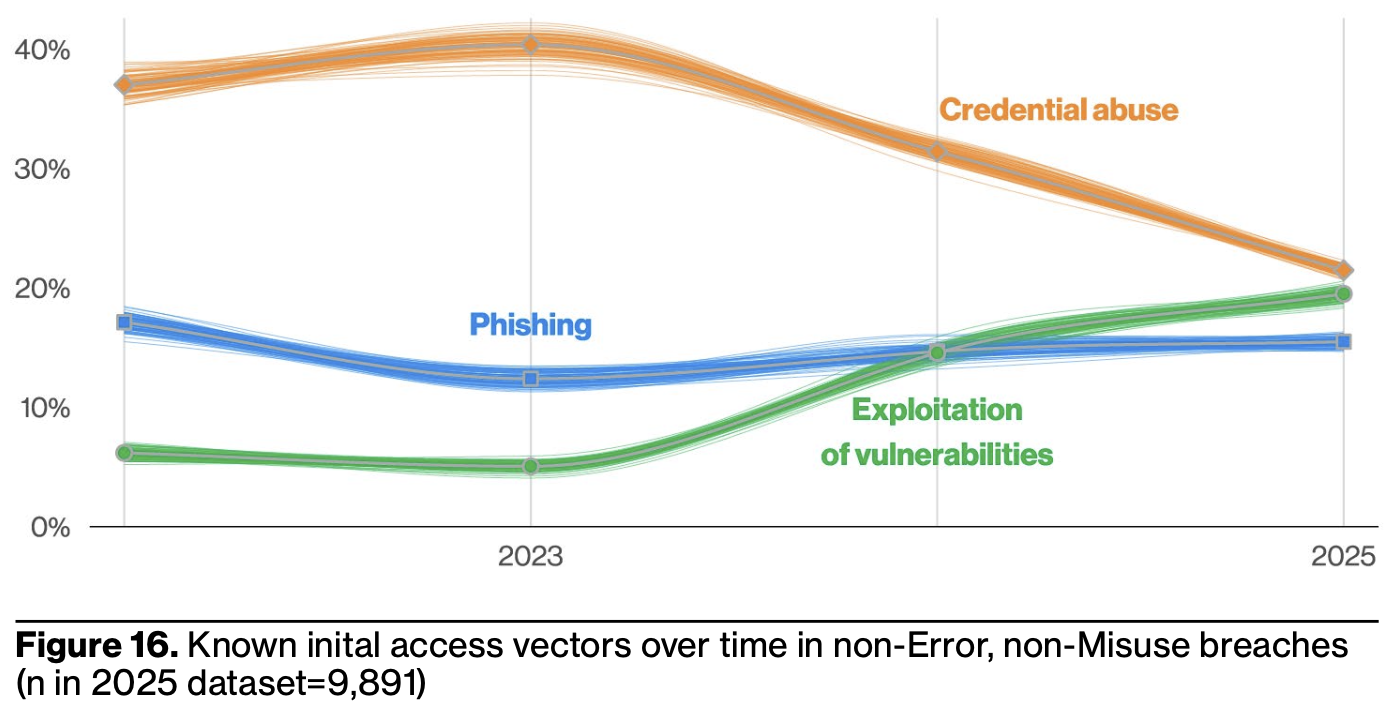

The industry obsesses over 0day17, but the 2025 DBIR shows only 8% of incidents involve vulnerabilities at all, and we must presume that even fewer of those involve zero day vulnerabilities (since, inherently, they decay into N-days once a patch releases).

Perhaps more surprising to readers is the report’s insight that not even APTs obsess exclusively over vulnerabilities (see also #3 on my list). Combing through code to uncover exploitable conditions is hard, and writing code to exploit those conditions and assumptions can be even harder. And if cybersecurity vendors will spend marketing dollars on publishing new exploitable vulns to the world, why not save a few bucks and co-opt their work?

My take is we should pay less attention to year-over-year changes and examine the longer-term trends more. The annual vagaries depend on what 0-days attackers or researchers discover, and how easy it is to write exploits for them vs. write patches for them. More precisely, all that really matters when it comes to 0day – or vulnerabilities in general – is how easy it is to turn them into a viable attack, where viable can refer to stealth, scale, consistency, and the other attributes I discussed in #2 on this list.

Consider the big topic from Verizon’s 2024 DBIR: MOVEit. MOVEit was a disaster because of their deployment model, tech-unsavvy customer base, and product proximity to ransomable data. In this year’s DBIR, system intrusion campaigns seem to be frolicking with credential abuse, phishing, BWAA – so any vulns that pop up are a bonus.18

This is an important finding to internalize from this year’s DBIR: use of stolen credentials continues to be a common attack pattern, because, to evoke Paul Hollywood from the Great British Bake-Off, it’s “simple, but effective.” It’s cheap, easy, and scales to large operations (the report notes that 80% of stolen accounts had prior exposure). Attackers might even learn to make friends in their Telegram chats along the way!

I find defenders often sleep on the potency of stolen creds, despite our general nihilism around nothing being secret anymore. The stolen cred problem is seen as “boring,” not one of those meaty technical problems into which you can sink your fangs and extract resume juice (jk, not jk).

To wit, even those infusing Secure by Design principles into how they secure their customers – a thoughtful endeavor, to be sure – may still overlook these “basic bitch” attacks. Snowflake, for example, invested considerable resources into isolating each tenant within their own separate VPC while supporting every cloud service provider19, only for those customers to get rocked by stolen credentials last year.

We should respect our opponents, but not aggrandize them. When threat modeling, assume they’ll follow Ina Garten’s advice: If you can’t make your own 0day, store-bought creds are fine.

7. Security was the real supply chain threat all along

Open source software (OSS) issues don’t even seem to be big enough to warrant a mention in the 2025 DBIR report. The only mention of OSS sits quietly in the news section towards the end, probably because talking heads and news outlets heavily report vulns in OSS due to the frankly bizarre level of distaste and disdain the traditional cybersecurity sphere feels towards OSS.

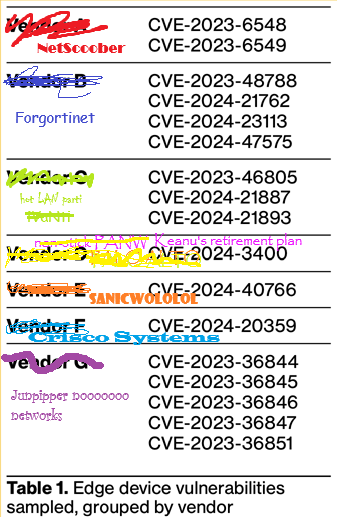

However, curiously, many of the vulns the DBIR lists as leading to incidents reside in what the report euphemistically refers to as “edge devices.” These are more accurately described as security appliances, as shown in the list I helpfully defaced below.

Perhaps the cybersecurity community should dog whistle less about the “insecure supply chain,” typically meaning open-source software, when OSS is akin to humans of code giving things away for free with no warranty. You get what you pay for.

It’s as if you raided someone’s house, tore out their wiring, then complained that the wiring was substandard copper… meanwhile your own house is stuffed with asbestos behind mercury walls.

8. Things Rot Apart

It’s 2025, and somehow VPNs and mail servers – the remnants of ye old ways where we had server janitors – persist in their ability to fuck your shit up. A simple security heuristic might be, “have you modernized or not yet?” where modernization means innovation hasn’t died and stunk up your stack like a decomposing skunk.

From that perspective, it is no surprise mail servers remain so prevalent in this data. Exchange is pooptacular (the technical term), but it’s also the best mail server out there, implying the remaining menagerie of mail servers are something like turbopooptacular20.

It’s been years since Google apps murdered any remaining innovation in running your own mail server. Typical exchanges (lolol) go something like:

“We have 20 years of investment sunk in this one mail server stack. Can we integrate some better security into it? Like, idk, even rsa tokens?”

“Absolutely not, because it needs to auth to legacy Outlook, which doesn’t support that.”

“…oh, okay.”

Being a computer janitor for big, chunky, clunky servers you run on-prem is a dying industry. No one is entering it. Students aren’t excited to maintain servers older than they are. There is no innovation left to squeeze from this spoiled, shriveled lime of a niche. For organizations still maintaining such servers, this means they cannot hire people to do it, and so it all rots.

What does it mean for tech to rot, to be rotten? Tech rots either due to neglect, or the world progressing faster than it does (or faster than its operators’ knowledge). Sometimes we see both transpire in sinister symbiosis.

Tech rots when it’s all operators know, and the newer world scares or intimidates them. It rots in restructurings, reductions in force, and other such euphemisms that result in new operators who don’t want to touch it for fear of breaking it – or perhaps such changes result in no owners at all.

When we analyze through this meta lens, the data shows that the new ways – those often met with so much resistance by the recalcitrant cyber reductionists – strongly correlate with better security outcomes. None of us should suffer under the yoke of rotten tech. We don’t have to settle. And we need not sleep restlessly at night, fearing insidious incidents and bowel-shattering breaches if we modernize our technology stacks.

Conversely, rotten tech seems to serve as a leading indicator of incidents and breaches. Why do corporate IT systems rot so badly? Can we prevent it? What other harm does the rot cause? This brings us to…

9. Scooby Doo’s Spooky Kooky Corporate IT Caper

It’s hard not to ponder the macro-level incident trends and see the spectre of corporate IT. Credential management, logins, vulnerable Blinky boxes, file transfer, email compromise, VPNs… for many organizations, security teams and their smorgasbord of cybersecurity vendor products fit under corporate IT.

These systems are poorly maintained and monitored, often years out of date. With such poor hygiene, should it surprise us that they’re more likely to succumb to attacks? Thankfully, many of these IT systems live on their own infrastructure and thus can only inflict limited damage.

Security systems, however, insist on embedding themselves in every other system: if it involves a computer, someone is going to want to stick EDR on it and send logs to a SIEM. These tools want the most privileges because that’s the easier design choice for them. Should an upgrade ever need to do more than it does today, they don’t require additional permissions because they already have them all.

Some of them are even designed to run arbitrary commands remotely, which is a sign that a piece of software might be hazardous to operate. This is such an obvious point to anyone who understands how computer systems work and yet eludes way too many security teams.

Being able to run arbitrary code is an exceptional thing for a system to do. Normal software systems don’t do that. The norm is for software systems to perform their function, and if that function ever changes, someone must upgrade the system with new software.

It is perhaps the antithesis of Secure by Design and Principle of Least Privilege, and it is fucking everywhere in security land – these “edge devices” included.

This is one reason, but not the only, why the gulf between corporate IT and software engineering is wide, widens, will keep widening. Such practices indicate a cultural canyon between the two spheres.

Modern software engineering practices explicitly seek to facilitate change, agility, adaptation in ways that corporate IT practices simply do not and cannot (and it’s why savvier security leaders transform their programs towards the former). In modern software engineering, updates are routine affairs involving many more components than corporate IT handles.

If we look at custom software engineering teams build – potentially even out of vulnerable open source components, gasp! – the DBIR data (and data elsewhere) shows that this custom software seldom leads to attackers breaching their organization.

When will we see the RSAC banners about traditionalist security teams not caring enough about software security replace those that fear monger about developers? Tribal narratives are powerful weapons to wield in propaganda. We should maintain intellectual integrity and call out poor software practices when we see them – ideally with constructive recommendations on how to improve – not simp for security vendors when they exhibit egregiously poor software practices.

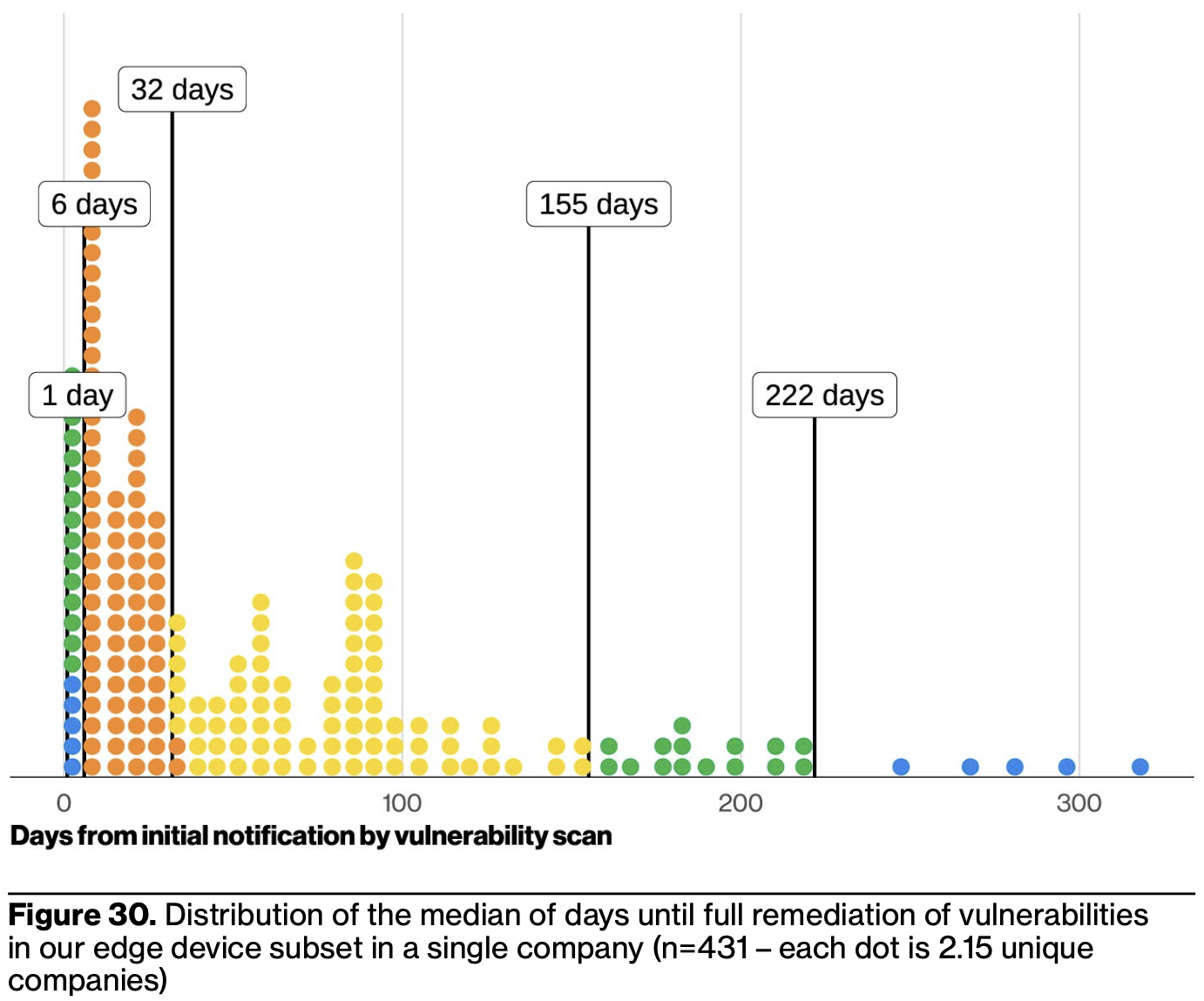

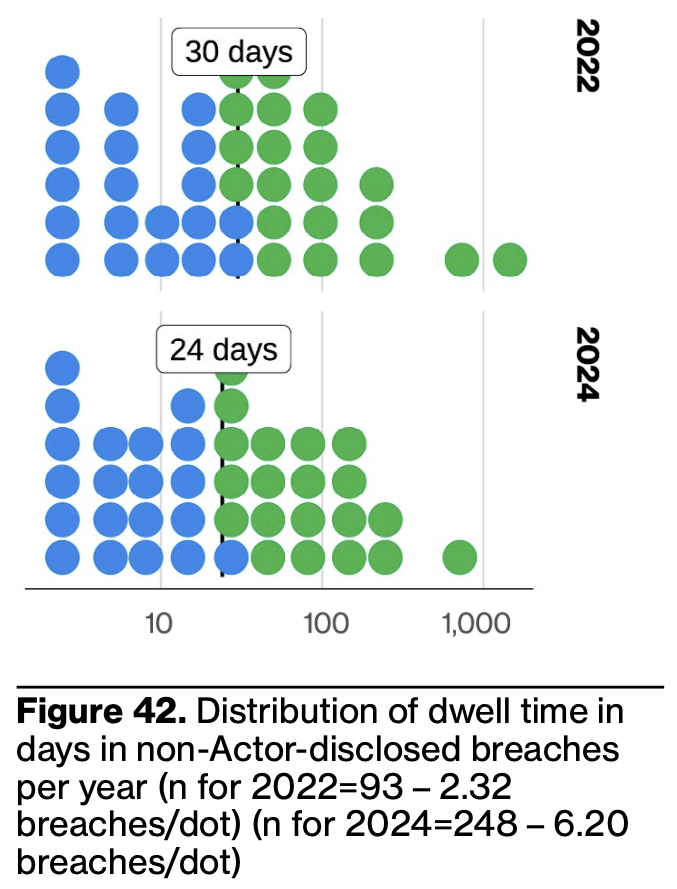

10. At least some things are improving somewhere

A bit of good news that deserves attention: dwell time is down by an entire week. This is a substantial decrease over only two years and suggests organizations have better mechanisms to tell when they’ve been breached.

It would be interesting to know what factors influence this improvement most. Is it primarily engendered by cybersecurity professionals / vendors leveling up their game, or does it arise from technology / architectural shifts (like those common in the fabled “digital transformation”)?

The 2025 DBIR observes a continued shift away from credit card data stolen in breaches, a trend we should also celebrate. I suspect it evinces the success of chip & PIN, as well as NFC (remember when the cyber industrial complex spewed a barrage of FUD about NFC payments and how it reflected the fraudpocalypse? Pepperidge Farm remembers).

The DBIR’s insight that Magecart represents 1% of System Intrusion breaches, but makes up 80% of payment card breaches suggests the latter has plummeted in volume. Now we just need digital payment wallets to really take off on desktop to render this category irrelevant.

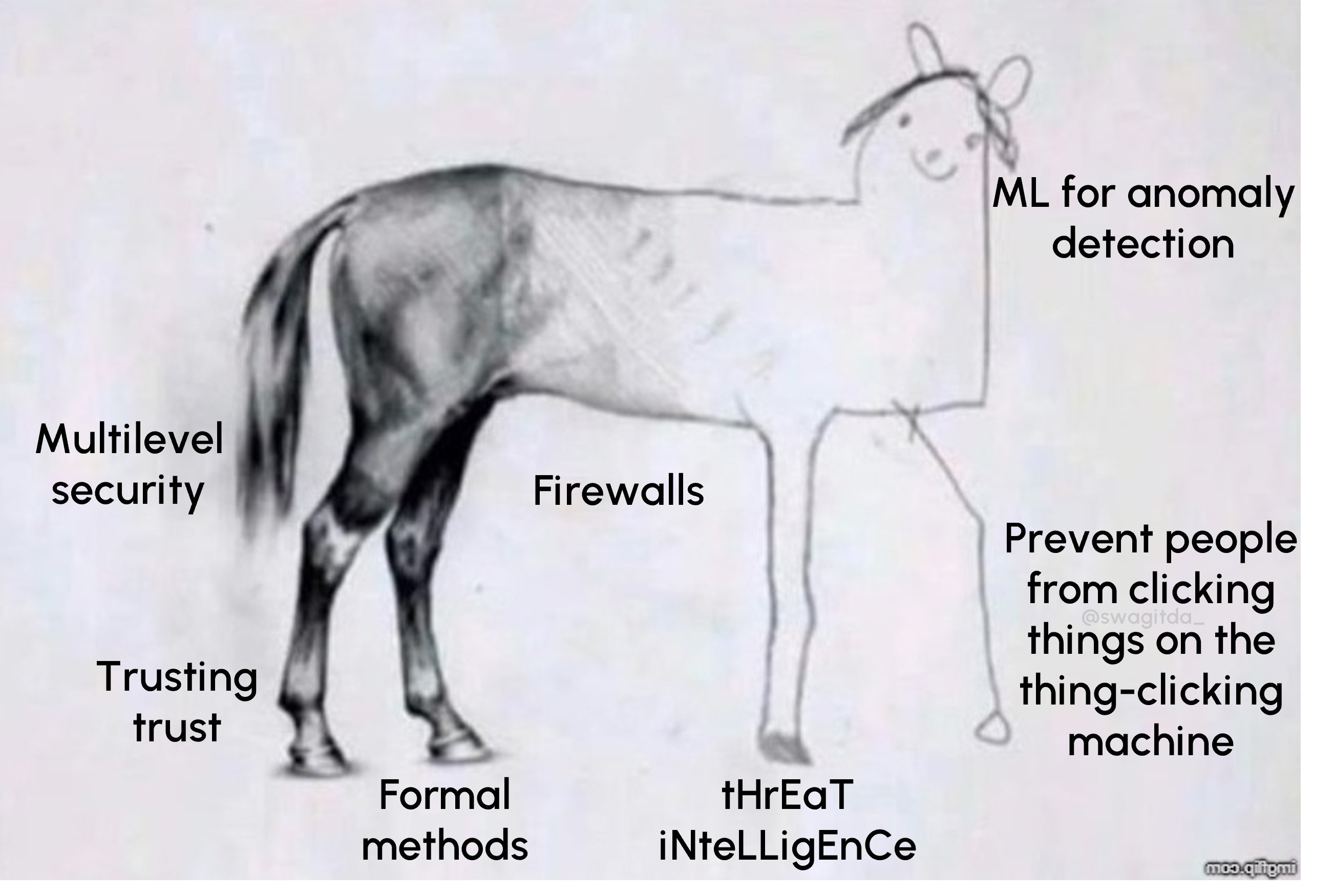

11. people continue to click things on the thing clicking machine

While the Verizon DBIR is far from the worst offender on this front, security reports often give off “you need to touch grass energy.” This is especially true when they touch topics related to humans clicking on things that facilitate incidents or breaches.

Users – the humans who interact with the technology we’ve made ubiquitous in their lives – expect to be able to click things and for the world not to implode. Clicking things is what many jobs are now. It should be safe to click links in the same way that it is safe to answer the phone.

The fact that it is not is an indictment of the security industry, not human behavior.

This allows me to send you off, dear reader, with one of my old memes, so we can depart back into the cybersecurity realm with a sense of enlightenment and, hopefully, humility.

thx AP <3

Enjoy this post? You might like my book, Security Chaos Engineering: Sustaining Resilience in Software and Systems, available at Bookshop, Amazon, and other major retailers online.

-

It’s a little cringe that the M-Trends report launched the same day as the DBIR’s widely publicized date. They should feel more confident in their own report and ensure it has a chance to shine; the competitive vibe isn’t the best look, when such reports should be in the spirit of leveling up the community. ↩︎

-

Indeed, throughout the report, one can feel the “data people with integrity feel anxiety about the data” vibes. This is a far better thing than the more pernicious “lying with data.” ↩︎

-

Imagine a sentient report, if you will, singing “What was I made for?” by Billie Eilish. Just replace “Just something you paid for” with “Just something you transmuted yourself into an MQL for.” ↩︎

-

I think it’s difficult to get an accurate ransomware total. We can see the total number of ransomware incidents they tracked: ~9703. However, I’m not sure what proportion they track in their dataset vs. miss. Of those 9703, 64% didn’t pay, leaving 3493. We only have the median, so it’s difficult to get to the aggregate amount paid in their dataset. If we work backwards from the median -> total calculation for BEC, which gives a 6.6 multiplier from median to mean, that suggests $2.66 billion in their dataset. A very very rough calculation. ↩︎

-

Is it more or less than the satisfaction a cyber reductionist CISO feels when wearing sweet APT-themed swag? ↩︎

-

Lockbit’s cumulative revenue hit at least $144 million in ransom payments between 2020 and the end of 2023. If I told you about a self-made startup founder who developed innovative SaaS technology and grew it to ~$50mm+ ARR in 3 years with zero VC funding, you’d be like, “who is this genius visionary??” It is a mistake to view attackers as genius, superhuman villains wielding silicon magic when they are, in practice, closer to shrewd tech entrepreneurs who identify product/market fit, execute on it by building software with iterative feature development, and successfully scale their operations to address market demand (and yes, sometimes that demand is espionage-flavored, as in “As an aspiring empire, we want to collect data from our primary adversary’s telecom providers so we can create richer profiles of key decision-makers in their government or, possibly, blackmail them.”). Game recognizes game14. ↩︎

-

I wonder if there’s a doc akin to the CIA’s Simple Sabotage Field Manual – their guide for disrupting progress in workplaces – but to disrupt your adversary’s attack groups by installing egotistical, smoke-blowing “leaders” who took a weekend MBA course and now think they are Frank Quattrone. ↩︎

-

see also how I solve every puzzle in The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom with the time reverse thingy ↩︎

-

if only more cyber reductionist security pros and linkedin thought leaders were “unwilling to remain medicore” ↩︎

-

Etymologically, however, sophisticated / sophistication served as a pejorative, related to the root word “sophists,” i.e. those who tell mellifluous, remunerative lies to eager ears. But the original original meaning indeed related to someone who is a master at their craft. ↩︎

-

To quote Rick Ross, “This shit is highly sophisticated, I just make it look easy” ↩︎

-

And this requires actually understanding what your business does, where it fits in your market, how it generates revenue, where it burns costs, and similar knowledge that traditionalist cybersecurity pros too often disdain. ↩︎

-

you can pry the desktop MS Office suite from my cold, dead hands tho. ↩︎

-

I bet Dmitry Khoroshev would know the answer(s). If you’re reading this, I’d love to “interview” you, if you know what I mean… ↩︎

-

I recall attending a security conference in a country stereotypically associated with prolific attack activity, and most attendees did not know what 2-factor authentication was. ↩︎

-

0day can be sexy, almost artistic in its manipulation of underlying machinations, but few that become public excite me. Annual reminder that I’ll go on a date with anyone who gives me a pre-auth RCE 0day in SSH. ↩︎

-

Magecart might be the exception, but I suspect the patching rate is quite low on the long tail of online retailers. ↩︎

-

the product people reading just gasped, I assure you. ↩︎

-

Gartner will likely label it “next-gen pooptacular” instead. ↩︎